Need Something More?

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Finding common ground is necessary to reach agreement on which goals will be set. The key is to establish goals together that are clear and specific, measurable, and attainable. Focus on setting goals that are meaningful and positive (e.g., focus on what you want, rather than what you don’t want).

When goals are broader and longer term, taking time to write down specific, measurable steps to attain your goal(s) is important. This allows you to understand the steps, track progress, and achieve success.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Disabled and Here (photo by Chona Kasinger) https://affecttheverb.com/disabledandhere/ (CC by 4.)

Weber, T., McKeever, J. E., & McDaniel, S. H. (1985). A beginner’s guide to the problem-oriented first family interview. Family Process, 24, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00357.x

If conflict resolution is a significant challenge in your relationship or if conflict escalation is a concern, please contact an appropriate support service. The Government of Canada provides a list of resources related to family violence and crisis services at the following link.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/services.html

Sometimes conflict can become negative and unproductive. Even happy couples will experience conflict where they say things they don’t mean, yell at one another, or shut down. Together, it is essential to figure out ways to effectively “repair” when needed, which means getting things back on track if a conflict is heading in a negative direction.

Using repair strategies that attempt to increase emotional closeness tend to be most helpful, which can include the following: 1,2

A foundation of friendship and respect is key. Taking the time to build and maintain a close, loving relationship helps with effectively managing conflict when it arises.

There are different ways to understand and define conflict resolution styles. Kurdek3 outlined four conflict resolution styles that individuals use when managing disagreement within their relationship. Click on the ![]() icons below to view examples of each conflict style:

icons below to view examples of each conflict style:

Consider these four conflict resolution styles outlined above and discuss the following:

The next skill building exercise focuses on making a plan to work toward more productive conflict resolution. Keep in mind your individual conflict resolution style(s) when doing the exercise.

Below is a questionnaire that provides examples of ways to repair if a conflict gets off track. You may find that some of the statements result in answers of “it depends”, which can be a good opportunity to reflect on your relationship and unique circumstances. Increasing awareness and having conversations about the strategies each of you use (or want to try) when resolving conflict can be helpful in developing healthy and productive approaches.

Questionnaire created by The Gottman Institute https://www.gottman.com/blog/weekend-homework-assignment-repair-attempts-2/ . Used with permission.

DOWNLOAD: Repair Attempts Questionnaire

After you have completed the questionnaire, discuss the following:

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Benson, K. (2022). Repair is the secret weapon of emotionally connected couples. The Gottman Institute. https://www.gottman.com/blog/repair-secret-weapon-emotionally-connected-couples/

1Gottman, J. M. (2015). The seven principles for making marriage work. Harmony.

2Gottman, J. M., Driver, J., & Tabares, A. (2015). Repair during marital conflict in newlyweds: How couples move from attack–defend to collaboration. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 26(2), 85-108. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2015.1038962

3Kurdek‚ L. A. (1994). Conflict resolution styles in gay‚ lesbian‚ heterosexual nonparent‚ and heterosexual parent couples. Journal of Marriage and Family‚ 56(3)‚ 705-722. https://doi.org/10.2307/352880

Kurdek, L. A. (1995). Predicting change in marital satisfaction from husbands’ and wives’ conflict resolution styles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(1), 153-164. https://doi.org/10.2307/353824

The Gottman Institute. (2022). Homework assignment: Repair attempts. https://www.gottman.com/blog/weekend-homework-assignment-repair-attempts-2/

Focusing on the quality of time spent together can be helpful. One way to do this is to pay full attention to each other during couple time. Try having your together time in a quiet and/or comfortable environment with limited distractions. You might want to dim the lights and share special food or drinks that you both enjoy. Limiting distractions can enhance intimacy. Be mindful to stay in the present moment and focus on each other. Minimize cell phone use/texting during this time. Constant texting can take focus away from your partner and have a negative impact on intimacy and your romantic relationship.

Intentionally creating positive interactions with each other is another way to enhance time spent together. This can include giving compliments, accommodating each other’s wishes, being cheerful, and/or using humour.

Together take a moment to reflect on how much quality time you spend with each other.

What are some ways you can increase quality time with your partner?

Take a moment to each write down 5 small things that you enjoy doing with your partner (either on a scrap of paper or take turns using the fillable form below). Don’t show your partner your list quite yet! Your list can include any activity that brings feelings of joy, intimacy, connection, or appreciation. Consider the day-to-day moments that are meaningful to you as a couple. They can be sharing a hug or kiss every day before work or bedtime, having a cup of coffee together, sharing a special meal or drink, going for a walk, talking about your day, etc.

Take a moment to each write down 5 small things that you enjoy doing with your partner (either on a scrap of paper or take turns using the fillable form below). Don’t show your partner your list quite yet! Your list can include any activity that brings feelings of joy, intimacy, connection, or appreciation. Consider the day-to-day moments that are meaningful to you as a couple. They can be sharing a hug or kiss every day before work or bedtime, having a cup of coffee together, sharing a special meal or drink, going for a walk, talking about your day, etc.

After you have both completed your lists, exchange them. Review your partner’s list and choose one thing that you each would like to commit to doing for one week.

After one week of doing these activities, reflect on the following together:

Over time, these small moments can become habits that strengthen relationships. Continue to check in with each other at the end of each week to ensure that you prioritize this time together, talk about how things are going, and adjust as needed. Creating small moments doesn’t take much time but it does take effort to develop new habits. It is important for both partners to commit to “small moments” to reap the benefits.

.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

1Roth, S.G., & Moore, C. D. (2009). Work-family fit: The impact of emergency medical services work on the family system. Prehospital Emergency Care, 13(4), 462-468. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120903144791

2Bochantin, J. E. (2016). “Morning fog, spider webs, and escaping from Alcatraz”: Examining metaphors used by public safety employees and their families to help understand the relationship between work and family. Communication Monographs, 83(2), 214-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1073853

3Gottman, J. M., & Silver, N. (2015). The seven principles for making marriage work. Harmony.

Halpern, D., & Katz, J. E. (2017). Texting’s consequences for romantic relationships: A cross-lagged analysis highlights its risks. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 386–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.051

Linnet, J. T. (2011). Money can’t buy me hygge: Danish middle-class consumption, egalitarianism, and the sanctity of inner space. Social Analysis, 55(2), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2011.550202

The Gottman Institute. (2022). How to turn your relationship goals into habits. The Gottman Institute. https://www.gottman.com/podcast/

Being able to express and talk about how we are feeling takes practice. Reviewing Speaking and Listening Skills can be helpful. Some couples find it easier to communicate about certain emotions compared to others. Consider the following:

Being aware of our feelings is an important first step in communicating how we feel. Labelling emotions may seem straightforward but can be challenging at times. Finding the right words can help us better understand our emotional experience and help communicate with others.

Sometimes feelings can be complex, and the feeling we immediately identify with and express may be made up of other underlying feelings (e.g., expressing anger when we are scared, hurt, or jealous). Also, we can experience more than one feeling at the same time.

The Feeling Wheel is a tool that can be used to describe feelings in a more detailed and accurate way. It includes six core emotions in the center of the wheel. More detailed emotions related to the core emotions are listed in the middle and outer circles. It does not include all possible feelings, so feel free to make note of any additional feeling words you may want to use.

Give it a try:

Was labelling your emotions easier or more difficult than you first expected? What did you both learn by practicing the skills of recognizing and labelling emotions?

G. Willcox. The Feeling Wheel. Used with permission from The Gottman Institute.

When it comes to communicating feelings, couples have both strengths and areas that they would like to improve. Communication about emotions takes continuous practice. Taking time to practice effective communication is an investment in maintaining a healthy relationship.

Both sharing feelings and “just listening” can be surprisingly difficult. To practice both sets of skills, try the following:

Exercise adapted from: “Dealing with Feelings” chapter in The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook [7th ed.], by Edmund Bourne, Ph.D.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Bourne, E. J. (2020). The anxiety and phobia workbook (7th ed). New Harbinger Publications.

Wilcox, G. (2020). The Feeling Wheel. Positive Psychology Practitioner’s Toolkit. https://www.gnyha.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/The-Feeling-Wheel-Positive-Psycology-Program.pdf

Willcox, G. (1982). The feeling wheel: A tool for expanding awareness of emotions and increasing spontaneity and intimacy. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12(4), 274-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215378201200411

If you are experiencing significant worry or anxiety that interferes with your day-to-day life (e.g., work, relationships, sleep, or other important parts of your life), it is recommended that you consult your health care provider. For additional information about anxiety visit: Anxiety Canada.

Free, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) courses for managing anxiety, as well as other mental health concerns, are available for both PSP and SSOs (spouses or significant others) who live in Canada. For more information, click here.

Couples might find it helpful to set aside time to have an open conversation about worries. This can include discussing feelings and asking questions and learning about the PSP’s job, the risks involved, and information about PSP training and safety protocols.

It may be useful to consider the following story about Chantal and Jean-Paul. They are fictional characters, but their story comes from real experiences that PSP families have shared. This story begins early in the relationship and illustrates some of the worries and challenges that PSP couples can face. As you watch the video below (around 4 minutes) about Chantal and Jean-Paul, consider your own story, the changes that have occurred, and the ways you have adjusted to this way of life.

Think about your own story and the way you have adapted to this way of life.

Consider changes that could make things better and share with your partner. It can be helpful to revisit these questions every few months, as people and situations change.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Sharp, M.-L., Solomon, N., Harrison, V., Gribble, R., Cramm, H., Pike, G., & Fear, N. T. (2022). The mental health and wellbeing of spouses, partners and children of emergency responders: A systematic review. Plos One, 17(6), e0269659. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269659

The recommended amount of sleep is 7-9 hours/night for healthy adults, although the optimal amount of sleep can vary depending on the person.1 The environment, daily habits, and pre-sleep routines can have an impact on amount and quality of sleep. See Skill Building below for information to support better sleep.

Life can get busy and it’s sometimes hard to find the time to get adequate sleep.

Many of the tips provided in the Skill Building section can still be useful during short-term periods with limited sleep to help you get the most out of the time you have.

If your sleep problems are associated with concerns such as stress, anxiety, or low mood, please click here for additional information about the Spouse Wellbeing Course (for spouses or significant others of PSP). This is a free, self-guided course for managing stress and various mental health concerns, as well as offering additional information and strategies to help improve sleep.

Getting enough sleep can be especially challenging for those who work rotating shifts, night shifts, or on-call shifts.

|

The following exercise is designed to help both partners identify good sleep habits and areas for improvement. Being aware of habits that benefit (or interfere with) sleep is an important step in supporting better sleep.

This exercise can be done individually or together. If completing this together, each of you can take a turn answering the questions on the slides below and discuss afterward. Sleep information and tips will be provided. (Note: some of the information and tips may need to be adjusted for those who work shift work.)

Below, there are 17 questions about your sleep habits. Answer the question on each slide by clicking either “yes” or “no” or skip a slide that is not applicable to you by pressing the right arrow at the bottom of the slide. Suggestions will appear regarding the benefits of certain habits, however, there are no right or wrong answers. Some suggestions may not be practical depending on your circumstances.

At the end of the activity, a summary is provided with your answers. You can print this summary by clicking on the print icon ![]() located on the bottom of the activity. Think about the questions that you answered “no” to, is there anything that you can change to improve your sleep habits? You can use the summary to set goals.

located on the bottom of the activity. Think about the questions that you answered “no” to, is there anything that you can change to improve your sleep habits? You can use the summary to set goals.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

1Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., DonCarlos, L., Hazen, N., Herman, J., Katz, E. S., Kheirandish-Gozal, L., Neubauer, D. N., O’Donnell, A. E., Ohayon, M., Peever, J., Rawding, R., Sachdeva, R. C., Setters, B., Vitiello, M. V., Ware, J. C., & Adams Hillard, P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep health, 1(1), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010

Bootzin, R. R., & Epstein, D. R. (2011). Understanding and treating insomnia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 435-458. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091516

Dumont, M. (2019). Coping better with night work: Interactive web tutorial. http://formations.ceams-carsm.ca/night_work/

Lammers-van der Holst, H. M., Murphy, A. S., Wise, J. (2020). Sleep tips for shift workers in the time of pandemic. Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care, 20(4), 128-130. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7189699/

Luyster, F. S., Strollo, P. J., Jr., Zee, P. C., & Walsh, J. K. (2012). Sleep: A health imperative. Sleep, 35(6), 727-734. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1846

National Sleep Foundation. Retrieved from www.thensf.org

Richter, K., Adam, S., Geiss, L., Peter, L., & Niklewski, G. (2016). Two in a bed: The influence of couple sleeping and chronotypes on relationship and sleep. An overview. Chronobiology International, 33(10), 1464-1472. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2016.1220388

Silberman, S. A. (2008). The insomnia workbook: A comprehensive guide to getting the sleep you need. New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Sleep Foundation. Retrieved from: www.sleepfoundation.org

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2021). Napping, an important fatigue countermeasure. CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/emres/longhourstraining/napping.html

Troxel W. M. (2010). It’s more than sex: Exploring the dyadic nature of sleep and implications for health. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(6), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181de7ff8

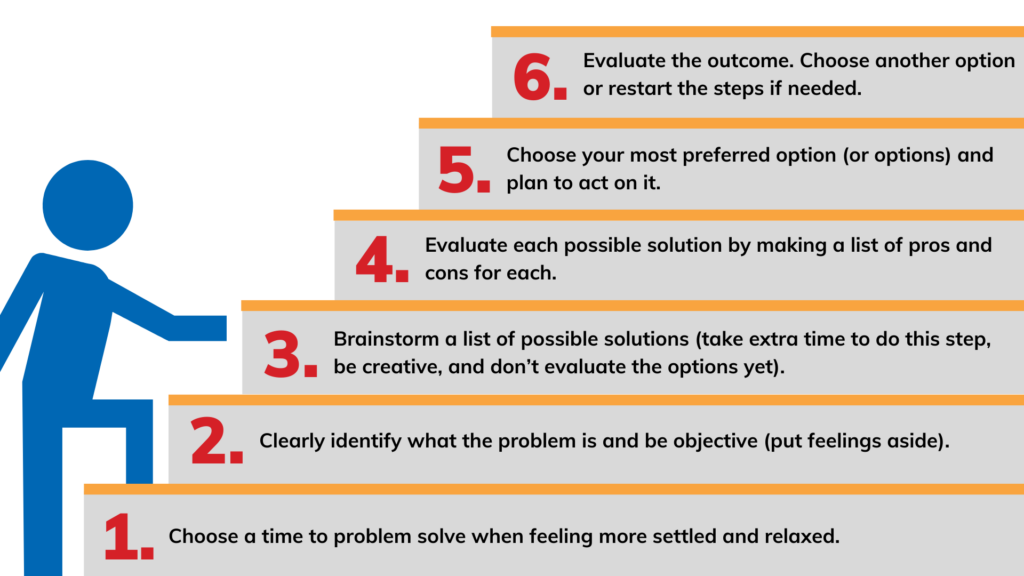

Working through a problem using the problem-solving steps below:

To start, practice these steps with simple everyday issues, then try these skills with more challenging problems.

Problem-solving steps can be done individually or as a couple. Practicing problem-solving skills can help navigate current issues and prevent future problems. When there are multiple problems to be solved, it is often better to tackle them one at a time.

When deciding to problem solve as a couple, consider what is required:

It can be helpful to think back to times when you have successfully problem solved together. How were you able to do this? What worked well for you as a couple?

When we are looking at problems, we don’t always get it right. Quick fixes don’t always address the bigger issues. For instance, cleaning up pee stains on the carpet won’t help if you don’t house train your pet. It can be helpful for couples to reflect on their current challenges, understand each other’s perspective, and explore possible solutions together.

Aliyah and Wong are a PSP couple that is experiencing some significant but not uncommon challenges. As you watch their story, think about some of the issues that they are facing and reflect on the questions at the end.

Planning date nights can be challenging, particularly for PSP couples with nonstandard schedules. The upside is that it can be a great way to practice problem-solving skills and also enjoy some couple time!

To give it a try, make a commitment together to plan a date night (or date morning/afternoon) at least once a week for the next month. The dates do not have to be big outings – at-home dates count too – so start with plans that are easier for you to make work. To begin, try the following:

After you have successfully negotiated your weekly date, take time to reflect on your experience problem solving together:

After one month, how did you do? You may want to continue scheduling date nights or come up with other ways to spend quality time together. Taking opportunities to practice problem solving as a couple is a way to improve these skills and strengthen your relationship.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Dattilio, F. M. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with couples and families: A comprehensive guide for clinicians. The Guilford Press.

Dattilio, F. M. & van Hout, G. C. M. (2006). The problem-solving component in cognitive-behavioral couples’ therapy. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 17(1), 1-19. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1300/J085v17n01_01

Indirect trauma exposure can occur when learning about a traumatic event that has happened to someone else. It can also happen to someone who provides support to a person who has been traumatized. The following table outlines signs and symptoms of indirect trauma. It is important to recognize these effects in ourselves and in others.

Experiencing a few of these symptoms for a short period of time may not be anything to worry about. However, if these symptoms persist and interfere with day to day activities, consultation with a mental health professional is recommended.

Note. Adapted from Preventing secondary traumatic stress disorder. In C.R. Figley (Ed.). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (1st ed.) (p. 169) by J. Yassen, 1995, Brunner Mazel. Adapted with author’s permission.

When it comes to talking about work-related traumatic events, setting boundaries about what to share and what not to share can help. Some couples find that not sharing the details about traumatic events is most helpful for them, while other couples have ground rules for sharing. It is important that you work together to establish boundaries that work for your relationship. Revisiting and renegotiating boundaries may also be needed as things change, particularly when a significant event has occurred or when there is noticeable tension that cannot be accounted for.

Working through these questions together can increase awareness of each partner’s experience, needs, and ways they feel supported. Open communication requires sensitivity and mutual respect for differences. Also keep in mind that situations and people change, and it may be useful to revisit this exercise in 6 months or a year.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

CIPSRT (2020). Glossary of Terms Vicarious Traumatization. CIPSRT-ICRTSP. https://www.cipsrt-icrtsp.ca/en/glossary/vicarious-traumatization

Garmezy, L. (2020). Swimming Upstream: The First Responder’s Marriage. In C. A. Bowers, & M. R. Marks (Eds.), Mental health intervention and treatment of first responders and emergency workers (pp. 16-31). Medical Information Science Reference/IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9803-9.ch002

Kim, J., Chesworth, B., Franchino-Olsen, H., & Macy, R. J. (2022). A scoping review of vicarious trauma interventions for service providers working with people who have experienced traumatic events. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(5), 1437-1460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021991310

Yassen, J. (1995). Preventing secondary traumatic stress disorder. In C.R. Figley (Ed.). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (1st ed.). (pp. 165-189). New York: Brunner Mazel.

(Adapted from “The Communication Styles Inventory (CSI): A Six-Dimensional Behavioral Model of Communication Styles and Its Relation With Personality” by R. E. de Vries, A. Bakker-Pieper, F. E. Konings, & B. Schouten, 2011, Communication Research, 40(4), 506-532.)

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Corcoran, J. (2005). Building strengths and skills: A collaborative approach to working with clients. Oxford University Press.

Dattilio, F. M. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with couples and families: A comprehensive guide for clinicians. The Guilford Press.

de Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., Konings, F. E., & Schouten, B. (2011). The communication styles inventory (CSI): A six-dimensional behavioral model of communication styles and its relation with personality. Communication Research, 40(4), 506-532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211413571

Note: It is not recommended that this strategy be used for trauma without the guidance of a qualified mental health professional.

Gratitude has been associated with strengthening personal relationships. Algoe and colleagues2 describe a find-remind-bind theory of gratitude. Expressing gratitude can find or initiate a new social relationship, remind people of existing relationships, and bind or strengthen relationships. Feeling and expressing gratitude plays an important role in maintaining relationships by promoting trust and lowering hostility.

How do you notice and appreciate the positive aspects of life? How do you express your gratitude for something or someone?

For the next four weeks, you and your partner commit to taking a few moments each day to write what you are grateful for in a journal or notebook. If possible, try to set a particular time each day (e.g., before you go to bed) to help make this exercise part of your routine. When writing about gratitude, consider:

For the next four weeks, you and your partner commit to taking a few moments each day to write what you are grateful for in a journal or notebook. If possible, try to set a particular time each day (e.g., before you go to bed) to help make this exercise part of your routine. When writing about gratitude, consider:

After four weeks, reflect on your experience. Has it been helpful? Sharing your gratitude journal with your partner and other family members can also be beneficial. You may want to create a couple or family gratitude journal so you can check-in, express appreciation, and inspire each other with positive thoughts.

Below is a list of situations that are often viewed as neutral or negative. Together, discuss each situation and fill in new, more positive ways to perceive each situation. Take turns and see how many “reframes” you can come up with for each situation. Next, you will have a chance to add your own situations that you can consider together.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

1Lambert, L. M., Graham, S. M., & Stillman, T. F. (2009). A changed perspective: How gratitude can affect sense of coherence through positive reframing. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6): 461–470). https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/17439760903157182

2Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8(3), 425–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425

Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., & Stillman, T. F. (2012). Gratitude and depressive symptoms: The role of positive reframing and positive emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 26(4), 615-633. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.595393

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005