Need Something More?

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Some families find that nonstandard hours allow them to accommodate childcare through tag-team parenting. The children are in the care of one or both of the parents most of the time. However, many PSP are required to report to work on short notice and work unscheduled overtime, which can be challenging to manage. For more information on managing challenges related to childcare, see Navigating the Childcare Scramble.

Good coparenting skills are essential when one or more parents work nonstandard hours and tag-team parenting is adopted. These skills include communication (Speaking and Listening Skills), problem solving (Problem Solving Together), and understanding and sharing parenting roles (Childcare). The following exercise may help you reflect on your coparenting skills and discuss with your partner(s) what each of you do well and areas for improvement.

In each of these coparent/child(ren) scenarios, think about how you have handled or how you might handle these types of situations, then check the next slide for a possible resolution. There are different ways to manage these situations – focus on what will bring about positive outcomes for the child(ren) and the entire family.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Feinberg, M. E., Boring, J., Le, Y., Hostetler, M. L., Karre, J., Irvin, J., & Jones, D. E. (2020). Supporting military family resilience at the transition to parenthood: A randomized pilot trial of an online version of family foundations. Family Relations, 69(1), 109-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12415

Paley, B., Lester, P., & Mogil, C. (2013). Family systems and ecological perspectives on the impact of deployment on military families. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(3), 245-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0138-y

Täht, K., & Mills, M. (2012). Nonstandard work schedules, couple desynchronization, and parent–child interaction: A mixed-methods analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 33(8), 1054-1087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11424260

Zhao, Y., Cooklin, A. R., Richardson, A., Strazdins, L., Butterworth, P., & Leach, L. S. (2021). Parents’ shift work in connection with work–family conflict and mental health: Examining the pathways for mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 42(2), 445-473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20929059

Communicating about worrisome, sad, or difficult topics can be challenging. Avoiding tough subjects does not help children or teens learn to manage worries and to accept that sad and bad things do happen. Age-appropriate discussions about the PSP job and risks can help children and teens worry less. If your child has concerns, understanding their point of view allows you to problem solve together and provide support. Below are tips for communicating with children and teens, particularly when dealing with difficult subjects.

It is normal for children and teens to worry or have some anxiety. Anxiety becomes a problem if it is intense, happens often, and makes it hard to do everyday activities. If you think that anxiety may be a problem for your child or teen, consult with your primary care provider or a qualified mental health professional.

For more information about anxiety in children and teens, visit:

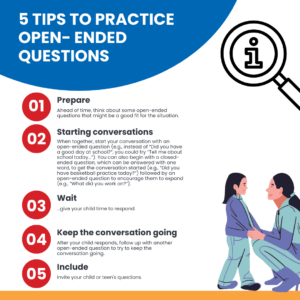

Open-ended questions or prompts tend to lead to more elaborate responses (not just a yes or no). These questions or statements can begin with how, why, who, what, where, when, or tell me about. Participate in the activity below to see if you can identify open-ended questions.

Using a variety of open-ended questions (or prompts), and waiting for a response, can take practice. During your next one-on-one conversation with your child or teen, try the following:

DOWNLOAD: Tips to Open-ended Questions

Afterward, consider the following: What was it like intentionally using open-ended questions with your child? What did you learn?

Once you have practiced using open-ended questions about everyday situations, begin asking open-ended questions related to PSP work or the lifestyle. The more you practice, the easier the skills of asking open-ended questions and listening will become. This can make it easier to initiate conversations about concerns or difficult topics, when needed.

Reading books or articles can be a great way to share information about PSP work and start conversations with your child or teen. For older children and teens, you may wish to share an age-appropriate article, blog post, or video on a PSP-related topic to provide information and start discussions. For example, you could share a newspaper article and say, “I read this article and was curious about your thoughts on this…” and follow up with an open-ended “What did you think?”

For young children, try the following:

After your shared reading time, reflect on this experience as a family. What was it like to read about the PSP role together? Are there other things you would like to learn about or talk about together?

Below are examples of children’s books about PSP:

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Arruda-Colli, M., Weaver, M. S., & Wiener, L. (2017). Communication about dying, death, and bereavement: A systematic review of children’s literature. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(5), 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0494 ;

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Cox, M., Norris, D., Cramm, H., Richmond, R., & Anderson, G. S. (2022). Public safety personnel family resilience: a narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095224 ;

Gurwitch, R. (2021). How to talk to children about difficult news. American Psychological Association. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/topics/journalism-facts/talking-children

Kolucki, B., & Lemish, D. (2011). Communication with children: Principles and practices to nurture, inspire, excite, educate and heal. UNICEF. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.comminit.com/global/content/communicating-children-principles-and-practices-nurture-inspire-excite-educate-and-heal

Traub, S. (2016). Communicating effectively with children. University of Missouri Extension. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://extension.missouri.edu/media/wysiwyg/Extensiondata/Pub/pdf/hesguide/humanrel/gh6123.pdf

Walker, J. R., & McGrath, P. (2013). Coaching for confidence workbook. Anxiety Disorders Association of Manitoba.

Wasik, B. A., & Hindman, A. H. (2013). Realizing the promise of open-ended questions. The Reading Teacher, 67(4), 302-311. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1218

Below is a comprehensive resource on self-care from the SSO Wellbeing Course. If you are interested in learning more about the SSO Wellbeing Course, click here.

This document is for individual, personal use only. To request permission for broader use, contact PSPNET.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Field, T. (2011). Yoga clinical research review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.09.007

Friese, K. M. (2020). Cuffed together: A study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 22(4), 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355720962527

Gál, É., Ștefan, S., & Cristea, I. A. (2021). The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 131-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.134

Hamasaki, H. (2020). Effects of diaphragmatic breathing on health: A narrative review. Medicines, 7(10), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines7100065

Huberty, J. L., Green, J., Puzia, M. E., Larkey, L., Laird, B., Vranceanu, A.-M., Vlisides-Henry, R., & Irwin, M. R. (2021). Testing a mindfulness meditation mobile app for the treatment of sleep-related symptoms in adults with sleep disturbance: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 16(1), e0244717. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244717

Kemper, K. J., & Danhauer, S. C. (2005). Music as therapy. Southern Medical Journal, 98(3), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.SMJ.0000154773.11986.39

Mayer, F. S., McPherson Frantz, C., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., & Dolliver, K. (2009). Why is nature beneficial?: The role of connectedness to nature. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 607-643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508319745

It is not uncommon to feel a sense of helplessness when plans are always changing and family routines are disrupted. Identifying potential opportunities associated with shiftwork and long hours is a way to reframe the experience and reduce stress. There are workarounds that families can adopt that make the changes and PSP absences less disruptive.

Think about your own flexibility when making plans.

Out of ideas? See below:

Family calendars are a key tool for coordinating family plans and activities. Take time together to consider the calendars that everyone in your household uses. Answering the following questions will get you thinking about how useful (or not) these calendars are and how to make them better.

Sometimes you can make order out of chaos. Keeping a central calendar for everyone in the household is a starting point. When unexpected changes occur, adjustments will be needed. Last minute changes can be challenging but are usually temporary and the family calendar can help everyone get back on track. You may even want to add back-up plans to your calendar, so these changes are less disruptive.

Let’s see how a PSP couple, Alejandro and Sofia, manage their busy schedule.

Click to visit a room, or click on the “![]() ” for more information.

” for more information.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Neustaedter, C., Brush, A., & Greenberg, S. (2009). The calendar is crucial: Coordination and awareness through the family calendar. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 16(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1145/1502800.1502806

Families who live together in the same house spend time together, but it may not always feel like quality time. When family members make a choice to do things together, this creates an opportunity to build mutual trust and commitment. Consider the following exercise to connect and strengthen family relationships and demonstrate the importance of family.

This is a list of several types of activities (for couples or families with children). Each family member checks the type of activities they want to do more of in the next 6 months. Look for matches. Two or more family members must be involved in the activity and make a commitment to participate. Each family member commits to participating in one activity and can participate in more than one activity. Family members work together to determine what the activity will be, when, and how it will be done.

Start small and aim for success! Consider the time and resources that you have to commit to the activity that you choose. Making a special dessert might be more achievable than preparing a four-course meal, though that might be your end goal. Keep in mind the time that is needed for preparation before you actually start the activity (e.g., deciding on games you want to play, buying the games, understanding instructions).

Every family has values, but they may underestimate their importance. Determining core values can help families recognize what they stand for and what matters most to them as a family. These shared values can be used to guide how families deal with challenges, including managing negative public perceptions and opinions. PSP family members often share beliefs about the role that the PSP performs and the importance of their shared commitment. When clearly understood, shared values about this way of life strengthen families. They can reinforce that “we’re in this together,” encourage open communication, and guide action when faced with adversity.

The purpose of this exercise is to discuss and identify your core family values. You may want to revisit your values in 3 to 6 months to see if they hold true or if other ones are more accurate.

Negative messages from the community and social media can be hurtful. Both adults and children in PSP families can be targeted. When this happens, open communication can reduce the negative effects. Families who share core values may be less impacted by misinformation. For example, a family who values “gratitude” can focus on the positive feedback they get from their community rather than negative messages. A shared commitment and understanding can help take the sting out of public criticism.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1088&context=dissertations

Carrington, J. L. (2006). Elements of and strategies for maintaining a police marriage: The lived perspectives of Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers and their spouses. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.itemid=NR18860&op=pdf&app=Library&is_thesis=1&oclc_number=289058279

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Witman, J. P., & Munson, W. W. (1992). Leisure Awareness & Action: A Program to Enhance Family Effectiveness. Journal of physical education, recreation & dance,63(8), 41-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1992.10609949

An awareness of the ways that social media and news coverage might negatively affect your family is a great way to start the conversation. Talking about potential problems encourages families to work together to manage the risks. Certain sectors of PSP are criticized on social media in ways that are not easy to ignore, and this can have different effects on family members. Open communication allows family members to share their experiences and discuss ways to respond when issues arise (e.g., explaining the facts to trusted friends and encouraging children to report bullying to parents and school authorities).

Social media is how many people stay connected to friends and events happening around the world. It is a popular and useful mode of communication for all ages. No one wants to toss away their phone or shut down the internet but, like many things in life, moderation is key. There is some evidence that overuse of social media is linked to poorer mental health generally and PSP families have additional concerns. Misinformation about PSP can start a chain of negative social media posts that are disturbing. There is also a risk of seeing images of events that a PSP family member is responding to which heightens worry. It is unlikely that we are going to put a stop to misinformation and videos that go viral but changing social media habits can reduce your exposure.

The following checklist items are suggestions for anyone trying to limit online activity, but they may be of particular interest to PSP families who are targeted by or sensitive to certain social media content.

Begin by answering the following reflection questions in the space provided and then use the checklist to assess what you are currently doing to limit your exposure to social media and things you might want to try. You will have an opportunity to download and print your list to share with other family members.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1088&context=dissertations

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

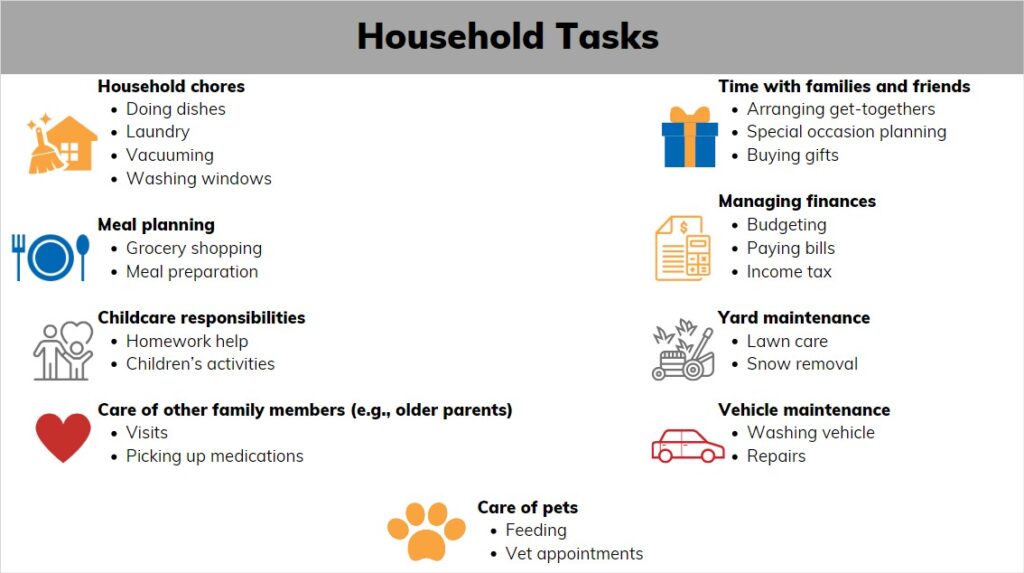

Recognition and appreciation of the ways that family members contribute to the household can reduce conflict. Many PSP families have busy households with a lot of demands on their time. Identifying and sharing household tasks can ensure that families also have time for leisure and rest.

A planned meeting as a couple/family can be an effective way to connect and make plans. You can use this time to discuss the division of household responsibilities and renegotiate if needed (see Household Tasks List below). It can also be a time to check in regarding how everyone is doing/feeling. You can make upcoming family plans, show appreciation to one another, or share exciting news or concerns. Family meetings are also opportunities to practice speaking and listening skills.

To have meetings that suit your family’s unique needs, consider the following:

Once you have decided on the frequency of meetings and considered everyone’s availability, schedule your meetings and make a commitment to attend. After each meeting, talk about what went well and potential changes for upcoming meetings.

Together, make a list of all your household tasks (e.g., housework, preparing meals, vehicle maintenance, children’s activities, appointments, managing finances, etc.). Note the specific responsibilities within each area, how long it typically takes to complete the task, and how often the task needs to be completed. The purpose of this exercise is to work toward dividing household tasks in a way that is a good fit for your family and your current situation. This is a chance to review the division of labour within your family to see if anything needs to shift or change.

When creating your list together, discuss:

Here is an example of household tasks to consider:

Below is a template for creating a Household Tasks List. You may want to create a customized list and display it where it can be viewed by the whole family. Use the download button to save and print your list.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Goldsmith, B. (2012, September 5). 10 tips for holding a family meeting: Hold the best meeting you’ll ever attend with the people you love the most. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/emotional-fitness/201209/10-tips-holding-family-meeting

Gottman, J.M. & Silver, N. (2015). The seven principles for making a marriage work. Harmony Books.

Petriglieri, J. (2019). Couples that work: How dual-career couples can thrive in love and work. Harvard Business Review Press.

Having conversations with family, friends, neighbours, and others who might be available to help with childcare needs is important. Who can watch the children if there is a shift change or a delay getting home from work (e.g., overtime, injury)? Who can help in the daytime? Overnight? Knowing your options ahead of time can help when plans change unexpectedly.

Use the Childcare Support List below to make a list of people who already – and might be able to – support your family. Beside each name, identify what type of support each person can provide. You can download and print your completed list.

When adding details to your list, consider the following:

The following 4 scenarios are situations that PSP families with young children may find themselves in. A solution is described that takes into account the wellbeing of each parent and children and build on their decision-making skills. You will be able to reflect on each scenario and save or print your answers by exporting the text at the end of the skill building exercise.

*Sometimes low mood, depression, worry, and/or anxiety can make it difficult to ask for help from others. The SSO Wellbeing Course can be a valuable resource to work through emotions related to asking for help.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Carillo, D., Harknett, K., Logan, A., Luhr, S., & Schneider, D. Instability of work and care: How work schedules shape child-care arrangements for parents working in the service sector. Social Service Review, 91(3), 422-455. https://doi.org/10.1086/693750

Lero, D. S., Prentice, S., Friendly, M., Richardson, B., & Fraser, L. (2019). Non-standard work and childcare in Canada: A challenge for parents, policy makers, and childcare provision. Childcare Resource and Research Unit and University of Guelph. https://childcarecanada.org/publications/other-publications/21/06/non-standard-work-and-child-care-canada-challenge-parents

Couples can support each other by having conversations to better understand each other’s expectations and needs when transitioning from work to home and home to work. Discussing what each partner finds helpful, especially on challenging days, allows couples to work together to negotiate a plan to support transitions. Think about how you typically navigate transition times together. The following skill building exercises will help you make a plan to support your transition times.

Together, discuss the following questions:

It can be helpful to communicate your level of distress during transition times. The following steps outline skills that allow for effective communication and planning:

Take a moment to focus on how you are feeling during transition times.

For example: Is there tension in your body? Are you able to focus? How reactive are you? etc.

Some people find it helpful to communicate by rating the level of distress on a scale of 1 (no distress) to 10 (very high distress). Others come up with a brief way to communicate a high level of distress.

For example: Saying, “I’ve had a bad shift, I’m going to come home and give you a hug, but then I’m going to need some time alone to unwind.”

Together, negotiate a plan for what transition times will look like when a high level of distress has been communicated.

For example: A PSP family member or SSO might put an object on the kitchen table (upside down coffee cup) as a non-verbal cue that the day has been difficult, and they need some time to recover (e.g., put the headphones on and listen to music or go for a run).

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., Mason, J., Ricciardelli, R., McCreary, D., Vaughan, A., Anderson, G. S., Krakauer, R., Donnelly, E. A., Camp II, R., Groll, D., Cramm, H., MacPhee, R., & Griffiths, C. (2020). Assessing the relative impact of diverse stressors among public safety personnel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041234

McElheran, M., & Stelnicki, A. M. (2021). Functional disconnection and reconnection: An alternative strategy to stoicism in public safety personnel. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1869399

Read through the Planning Checklist together. The aim of the checklist is to assess what plans you already have in place and things to consider going forward.

Once you have assessed your situation and needs, it is time to make some decisions about what you want to do. Talk about how you feel about making these plans and consider the benefits of planning ahead. Then make some practical decisions about what items you want to address and how this will get done.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. (2017, April 28). 11.4 Estate planning. https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/services/financial-toolkit/financial-planning/financial-planning-4.html