Need Something More?

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Some families find that nonstandard hours allow them to accommodate childcare through tag-team parenting. The children are in the care of one or both of the parents most of the time. However, many PSP are required to report to work on short notice and work unscheduled overtime, which can be challenging to manage. For more information on managing challenges related to childcare, see Navigating the Childcare Scramble.

Good coparenting skills are essential when one or more parents work nonstandard hours and tag-team parenting is adopted. These skills include communication (Speaking and Listening Skills), problem solving (Problem Solving Together), and understanding and sharing parenting roles (Childcare). The following exercise may help you reflect on your coparenting skills and discuss with your partner(s) what each of you do well and areas for improvement.

In each of these coparent/child(ren) scenarios, think about how you have handled or how you might handle these types of situations, then check the next slide for a possible resolution. There are different ways to manage these situations – focus on what will bring about positive outcomes for the child(ren) and the entire family.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Feinberg, M. E., Boring, J., Le, Y., Hostetler, M. L., Karre, J., Irvin, J., & Jones, D. E. (2020). Supporting military family resilience at the transition to parenthood: A randomized pilot trial of an online version of family foundations. Family Relations, 69(1), 109-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12415

Paley, B., Lester, P., & Mogil, C. (2013). Family systems and ecological perspectives on the impact of deployment on military families. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(3), 245-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0138-y

Täht, K., & Mills, M. (2012). Nonstandard work schedules, couple desynchronization, and parent–child interaction: A mixed-methods analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 33(8), 1054-1087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11424260

Zhao, Y., Cooklin, A. R., Richardson, A., Strazdins, L., Butterworth, P., & Leach, L. S. (2021). Parents’ shift work in connection with work–family conflict and mental health: Examining the pathways for mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 42(2), 445-473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20929059

Communicating about worrisome, sad, or difficult topics can be challenging. Avoiding tough subjects does not help children or teens learn to manage worries and to accept that sad and bad things do happen. Age-appropriate discussions about the PSP job and risks can help children and teens worry less. If your child has concerns, understanding their point of view allows you to problem solve together and provide support. Below are tips for communicating with children and teens, particularly when dealing with difficult subjects.

It is normal for children and teens to worry or have some anxiety. Anxiety becomes a problem if it is intense, happens often, and makes it hard to do everyday activities. If you think that anxiety may be a problem for your child or teen, consult with your primary care provider or a qualified mental health professional.

For more information about anxiety in children and teens, visit:

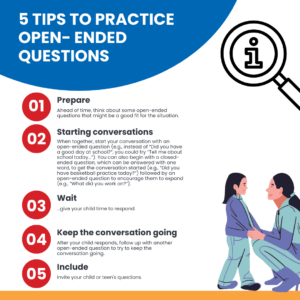

Open-ended questions or prompts tend to lead to more elaborate responses (not just a yes or no). These questions or statements can begin with how, why, who, what, where, when, or tell me about. Participate in the activity below to see if you can identify open-ended questions.

Using a variety of open-ended questions (or prompts), and waiting for a response, can take practice. During your next one-on-one conversation with your child or teen, try the following:

DOWNLOAD: Tips to Open-ended Questions

Afterward, consider the following: What was it like intentionally using open-ended questions with your child? What did you learn?

Once you have practiced using open-ended questions about everyday situations, begin asking open-ended questions related to PSP work or the lifestyle. The more you practice, the easier the skills of asking open-ended questions and listening will become. This can make it easier to initiate conversations about concerns or difficult topics, when needed.

Reading books or articles can be a great way to share information about PSP work and start conversations with your child or teen. For older children and teens, you may wish to share an age-appropriate article, blog post, or video on a PSP-related topic to provide information and start discussions. For example, you could share a newspaper article and say, “I read this article and was curious about your thoughts on this…” and follow up with an open-ended “What did you think?”

For young children, try the following:

After your shared reading time, reflect on this experience as a family. What was it like to read about the PSP role together? Are there other things you would like to learn about or talk about together?

Below are examples of children’s books about PSP:

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Arruda-Colli, M., Weaver, M. S., & Wiener, L. (2017). Communication about dying, death, and bereavement: A systematic review of children’s literature. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(5), 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0494 ;

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Cox, M., Norris, D., Cramm, H., Richmond, R., & Anderson, G. S. (2022). Public safety personnel family resilience: a narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095224 ;

Gurwitch, R. (2021). How to talk to children about difficult news. American Psychological Association. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/topics/journalism-facts/talking-children

Kolucki, B., & Lemish, D. (2011). Communication with children: Principles and practices to nurture, inspire, excite, educate and heal. UNICEF. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.comminit.com/global/content/communicating-children-principles-and-practices-nurture-inspire-excite-educate-and-heal

Traub, S. (2016). Communicating effectively with children. University of Missouri Extension. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://extension.missouri.edu/media/wysiwyg/Extensiondata/Pub/pdf/hesguide/humanrel/gh6123.pdf

Walker, J. R., & McGrath, P. (2013). Coaching for confidence workbook. Anxiety Disorders Association of Manitoba.

Wasik, B. A., & Hindman, A. H. (2013). Realizing the promise of open-ended questions. The Reading Teacher, 67(4), 302-311. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1218

Below is a comprehensive resource on self-care from the SSO Wellbeing Course. If you are interested in learning more about the SSO Wellbeing Course, click here.

This document is for individual, personal use only. To request permission for broader use, contact PSPNET.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Field, T. (2011). Yoga clinical research review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.09.007

Friese, K. M. (2020). Cuffed together: A study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 22(4), 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355720962527

Gál, É., Ștefan, S., & Cristea, I. A. (2021). The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 131-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.134

Hamasaki, H. (2020). Effects of diaphragmatic breathing on health: A narrative review. Medicines, 7(10), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines7100065

Huberty, J. L., Green, J., Puzia, M. E., Larkey, L., Laird, B., Vranceanu, A.-M., Vlisides-Henry, R., & Irwin, M. R. (2021). Testing a mindfulness meditation mobile app for the treatment of sleep-related symptoms in adults with sleep disturbance: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 16(1), e0244717. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244717

Kemper, K. J., & Danhauer, S. C. (2005). Music as therapy. Southern Medical Journal, 98(3), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.SMJ.0000154773.11986.39

Mayer, F. S., McPherson Frantz, C., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., & Dolliver, K. (2009). Why is nature beneficial?: The role of connectedness to nature. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 607-643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508319745

It is not uncommon to feel a sense of helplessness when plans are always changing and family routines are disrupted. Identifying potential opportunities associated with shiftwork and long hours is a way to reframe the experience and reduce stress. There are workarounds that families can adopt that make the changes and PSP absences less disruptive.

Think about your own flexibility when making plans.

Out of ideas? See below:

Family calendars are a key tool for coordinating family plans and activities. Take time together to consider the calendars that everyone in your household uses. Answering the following questions will get you thinking about how useful (or not) these calendars are and how to make them better.

Sometimes you can make order out of chaos. Keeping a central calendar for everyone in the household is a starting point. When unexpected changes occur, adjustments will be needed. Last minute changes can be challenging but are usually temporary and the family calendar can help everyone get back on track. You may even want to add back-up plans to your calendar, so these changes are less disruptive.

Let’s see how a PSP couple, Alejandro and Sofia, manage their busy schedule.

Click to visit a room, or click on the “![]() ” for more information.

” for more information.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Neustaedter, C., Brush, A., & Greenberg, S. (2009). The calendar is crucial: Coordination and awareness through the family calendar. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 16(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1145/1502800.1502806

Families who live together in the same house spend time together, but it may not always feel like quality time. When family members make a choice to do things together, this creates an opportunity to build mutual trust and commitment. Consider the following exercise to connect and strengthen family relationships and demonstrate the importance of family.

This is a list of several types of activities (for couples or families with children). Each family member checks the type of activities they want to do more of in the next 6 months. Look for matches. Two or more family members must be involved in the activity and make a commitment to participate. Each family member commits to participating in one activity and can participate in more than one activity. Family members work together to determine what the activity will be, when, and how it will be done.

Start small and aim for success! Consider the time and resources that you have to commit to the activity that you choose. Making a special dessert might be more achievable than preparing a four-course meal, though that might be your end goal. Keep in mind the time that is needed for preparation before you actually start the activity (e.g., deciding on games you want to play, buying the games, understanding instructions).

Every family has values, but they may underestimate their importance. Determining core values can help families recognize what they stand for and what matters most to them as a family. These shared values can be used to guide how families deal with challenges, including managing negative public perceptions and opinions. PSP family members often share beliefs about the role that the PSP performs and the importance of their shared commitment. When clearly understood, shared values about this way of life strengthen families. They can reinforce that “we’re in this together,” encourage open communication, and guide action when faced with adversity.

The purpose of this exercise is to discuss and identify your core family values. You may want to revisit your values in 3 to 6 months to see if they hold true or if other ones are more accurate.

Negative messages from the community and social media can be hurtful. Both adults and children in PSP families can be targeted. When this happens, open communication can reduce the negative effects. Families who share core values may be less impacted by misinformation. For example, a family who values “gratitude” can focus on the positive feedback they get from their community rather than negative messages. A shared commitment and understanding can help take the sting out of public criticism.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1088&context=dissertations

Carrington, J. L. (2006). Elements of and strategies for maintaining a police marriage: The lived perspectives of Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers and their spouses. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.itemid=NR18860&op=pdf&app=Library&is_thesis=1&oclc_number=289058279

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Witman, J. P., & Munson, W. W. (1992). Leisure Awareness & Action: A Program to Enhance Family Effectiveness. Journal of physical education, recreation & dance,63(8), 41-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1992.10609949

We can understand resentment as a mixture of feelings of frustration, anger, envy, and sadness. This emotion can surface when we feel things are unfair or unjust, or if we fail to set boundaries, or we feel let down. It is usually not a single event but multiple events that build up over time. Resentment can make us feel ill about something that we think is wrong. Resentment can be an individual or shared experience. It is a complex emotion that can be shaped by and shape other negative feelings like loneliness, fear, grief, etc.

PSP family members might feel resentment toward the PSP’s job requirements such as shiftwork or unscheduled overtime. PSP’s work is usually less flexible than typical jobs. Rotating and unpredictable shifts have to be accommodated. There could be resentment over the camaraderie/companionship the PSP has with coworkers. PSP family members have reported feeling resentment when the PSP job is prioritized and seems to be more important than family.

Resentment could result in:

PSP families have identified the many ways that the unpredictability of PSP work interferes with family life.

Over the years these experiences become ‘normal’ parts of daily life for PSP families. SSOs and other family members are expected to adapt. But, over time, with many changes and disruptions, SSOs can feel that they are taken for granted and ‘the job’ is more important.

Many PSP families understand, and many accept the risks and requirements of the job. However, the constant nature of the disruptions can pile up and become more than families can manage. The seemingly endless demands and the lack of recognition for the role of family members can be frustrating. Families feel resentment toward ‘the job’ which is central to tensions and conflicts that arise.

Alrutz, A. S., Buetow, S., Cameron, L. D., & Huggard, P. K. (2020). What happens at work comes home. Healthcare (Basel), 8(3), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030350

Black, A. (2004). The treatment of psychological problems experienced by the children of police officers in Northern Ireland. Child care in practice : Northern Ireland journal of multi-disciplinary child care practice, 10(2), 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270410001693330

Carrington, J. L. (2006). Elements of and strategies for maintaining a police marriage: The lived perspectives of Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers and their spouses. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Cigrang, J. A. et al. (2016). The Marriage Checkup: Adapting and Implementing a Brief Relationship Intervention for Military Couples. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 23, 561-570.

Cowlishaw, S., Evans, L., & McLennan, J. (2008). Families of rural volunteer firefighters. Rural Society, 18(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.351.18.1.17

Ewles, G. (2019). Enhancing organizational support for emergency first responders and their families: Examining the role of personal support networks after the experience of work-related trauma. PhD Thesis. University of Guelph.

Merolla, A. J. (2010). Relational maintenance during military deployment: Perspectives of wives of deployed US soldiers. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(1), 4–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880903483557

Miller, L. (2007). Police families: Stresses, syndromes, and solutions. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180600698541

Regehr, C. (2005). Bringing the trauma home: Spouses of paramedics. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 10(2), 97-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020590908812

Regehr, C., Dimitropoulos, G., Bright, E., George, S., & Henderson, J. (2005). Behind the brotherhood: Rewards and challenges for wives of firefighters. Family Relations, 54(3), 423-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00328.x

Roberts, N. A., & Levenson, R. W. (2001). The Remains of the Workday: Impact of Job Stress and Exhaustion on Marital Interaction in Police Couples. Journal of marriage and family, 63(4), 1052-1067. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01052.x

Watkins, S. L., Shannon, M. A., Hurtado, D. A., Shea, S. A., & Bowles, N. P. (2021). Interactions between home, work, and sleep among firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 64(2), 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23194

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Sleep can be disrupted for PSP families for a number of reasons. When PSP are at work, family members may have a hard time falling or staying asleep due to worry. The timing when PSP leave and return home can be out of sync with family members, interfering with their sleep and sleep routines. When PSP need to sleep in the day, family members change their activities to maintain quiet.

Both the shift work and the unpredictability of PSP work can interfere with sleep. In some PSP sectors, such as volunteer firefighting, there may be an expectation for a PSP to be on call often, leading to the possibility of call-ins at any time. This disrupts both their sleep and the sleep of their spouse/significant other (SSOs) and family members.

Unexpected call-ins and overtime can also lead to inconsistent schedules for children. Wake up, bedtimes, and nap times might get rearranged due to the unpredictability of PSP work.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Ananat, E. O. & Gassman-Pines, A. (2021). Work schedule unpredictability: daily occurrence and effect on working parents’ well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(1):10-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12696

Bochantin, J. E. (2010). Sensemaking in a high-risk lifestyle: The relationship between work and family for public safety families. PhD Thesis. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Cowlishaw, S., Evans, L., & McLennan, J. (2010). Work-family conflict and crossover in volunteer emergency service workers. Work & Stress, 24(4), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.532947

Cox, M., Norris, D., Cramm, H., Richmond, R., & Anderson, G. S. (2022). Public safety personnel family resilience: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095224

Friese, K. M. (2020). Cuffed together: A study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 22(4), 407-418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355720962527

Hill, R., Sundin, E., & Winder, B. (2020). Work–family enrichment of firefighters: “satellite family members”, risk, trauma and family functioning. International Journal of Emergency Services, 9(3), 395-407. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJES-08-2019-0046

Landers, A. L., Dimitropoulos, G., Mendenhall, T. J., Kennedy, A., & Zemanek, L. (2020). Backing the blue: Trauma in law enforcement spouses and couples. Family Relations, 69(2), 308-319. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12393

Regehr, C., Dimitropoulos, G., Bright, E., George, S., & Henderson, J. (2005). Behind the brotherhood: Rewards and challenges for wives of firefighters. Family Relations, 54(3), 423-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00328.x

Tuttle, B. M., Giano, Z., & Merten, M. J. (2018). Stress spillover in policing and negative relationship functioning for law enforcement marriages. The Family Journal (Alexandria, Va.), 26(2), 246-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480718775739

Watkins, S. L., Shannon, M. A., Hurtado, D. A., Shea, S. A., & Bowles, N. P. (2021). Interactions between home, work, and sleep among firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 64(2), 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23194

Public perceptions are the stories about PSP and PSP sectors that are commonly believed by the general public. These stories can quickly shift and change which can be frustrating for both PSP and their families. Movies and TV often portray PSP work as either glamorous or corrupt which can lead to misinformation about ‘the job’. Media and social media can also shift public perceptions in the way that they report stories involving PSP. Stereotypes create further misconceptions. Because of these factors, PSP families never know what to expect from the public.

PSP family members may also feel that they are being held to an impossible standard. For example, children may feel pressure to be ‘extra good’ because their parent is a police officer. These feelings might be stronger in rural communities, where community members are more likely to know each other.

Negative public perceptions can be very frustrating for PSP and for their families who sacrifice holidays, weekends, time, and personal safety to protect the community. It can be hurtful to know what a PSP family member does every day, and then hear negative things said about them. In some cases, negative public perceptions has lead to threats and safety concerns for PSP families.

Overall, because public perceptions can change so quickly, the importance of public perceptions – positive, negative, or absent – is felt by PSP families and can impact relationships and the wellbeing of individual family members.

Disdain is a feeling of dislike. It is often demonstrated through disrespect or contempt. PSP who are in positions of authority, such as police and corrections officers, are often targeted in this way. Current events, world news, and social trends can influence these negative perceptions.

Disdain is a feeling of dislike. It is often demonstrated through disrespect or contempt. PSP who are in positions of authority, such as police and corrections officers, are often targeted in this way. Current events, world news, and social trends can influence these negative perceptions.

Negative public perceptions can have a direct impact on PSP job satisfaction and the overall wellbeing of families.

Negative feedback from members of the public can challenge a PSP’s commitment and pride in their work. It can affect self-confidence and behaviours both at work and at home. This can lead to tension, uncertainty, and boundary confusion, experienced by PSP families. Families struggle with the negative feedback too. Negative public opinions can challenge beliefs and family values that are often related to the PSP role. PSP families may feel isolated from the rest of the community. A feeling of ‘us and them’ could develop resulting in a lack of social support.

Police children report receiving unfair comments and criticism about a PSP parent’s work. As children age, they sometimes grapple with negative comments from peers and social media. They might question the pride they once felt which can lead to ambivalence – they still believe in the importance of public safety but may resent the PSP or the ‘job’ because of the way they are treated.

Gratitude – When members of the public express gratitude to PSP and/or their families, they are showing their appreciation. This gratitude is welcomed by some PSP families who feel that it validates the importance of the PSP role. When gratitude is extended to other family members, the public is also acknowledging the contribution of PSP families.

Certain PSP sectors are shown to experience more gratitude than others. Firefighters are often publicly recognized for their bravery and service. Paramedics and similar emergency medical service careers are also often viewed positively by the public. PSP family members might also receive direct forms of praise from the public for the work their PSP member does (e.g., “thank you for the work your mother/father does”).

Positive public perceptions can be experienced as validation by PSP family members. If the public appreciates what the PSP does, then it can make all of the commitment and sacrifices feel worthwhile. Sometimes, however, gratitude is shown only to the PSP, and the roles of SSOs and other family members are not considered. When families are not recognized, they may feel that their contribution is not well understood.

PSP families who are viewed positively by the public may develop civic mindedness. They may be actively involved in their communities and feel a sense of pride in being recognized as a PSP family. This might, however, also increase pressure for PSP family members to live up to public expectations. Because the community shows appreciation, PSP families may feel obligated to do more. This can increase demands on their time.

PSP families benefit when communities value the important work that they do. Families sometimes feel out of sync with others due to work demands and public recognition is important. When PSP families are acknowledged, there is a positive sense of identity and belonging.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Bochantin, J. E. (2010). Sensemaking in a high-risk lifestyle: The relationship between work and family for public safety families. PhD Thesis. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Carrington, J. L. (2006). Elements of and strategies for maintaining a police marriage: The lived perspectives of Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers and their spouses. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Duarte, C. S., Eisenberg, R., Musa, G. J., Addolorato, A., Shen, S., & Hoven, C. W. (2017). Children’s knowledge about parental exposure to trauma. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(1), 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0159-7

Freeman, R. M. (2001). Here there be monsters: Public perception of corrections. Corrections Today, 63(3), 108-111.

Helfers, R. C., Reynolds, P. D., & Scott, D. M. (2021). Being a blue blood: A phenomenological study on the lived experiences of police officers’ children. Police Quarterly, 24(2), 233-261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611120964954

Majchrowska, A., Pawlikowski, J., Jojczuk, M., Nogalski, A., Bogusz, R., Nowakowska, L., & Wiechetek, M. (2021). Social prestige of the paramedic profession. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041506

McCubbin, H. I., & McCubbin, M. A. (1988). Typologies of resilient families: Emerging roles of social class and ethnicity. Family Relations, 37(3), 247-254. https://doi.org/10.2307/584557

Miller, L. (2007). Police families: Stresses, syndromes, and solutions. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180600698541

Nix, J., & Wolfe, S. E. (2017). The impact of negative publicity on police self-legitimacy. Justice Quarterly, 34(1), 84–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2015.1102954

Tucker, J. M., Bratina, M. P., & Caprio, B. (2022). Understanding the effect of news media and social media on first responders. Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience: An International Journal, 3(4) 106-137.

Walsh, F. (2003). Family Resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x

Woody, R. H. (2006). Family interventions with law enforcement officers. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 34(2), 95-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180500376735

Some PSP family members have identified the risk of physical and mental injury as their greatest worry.

The risk of injury or illness can create stress for the PSP. This stress can spill over into family life causing tension. At the same time, family members may also be fearful and worry about the dangers of the job. The wellbeing of the PSP family member, loss of income, and disruptions to family life are primary concerns. Open communication about the real risks and contingency plans can prevent worry from getting out of control.

Family members often become caregivers when a PSP is injured or ill. There may be physical demands associated with this care. Family caregivers may experience physical fatigue due to increased responsibilities. This can put their own health at risk and lead to role overload. The expectation that spouses or significant others (SSOs) or other family members will provide care is not always realistic. It is important for PSP couples and families to have conversations about caregiving.

When a family member is injured or ill, family life changes. There are worries along with added responsibilities for SSOs and other family caregivers. They may experience the emotional distress of ‘not being able to do it all’ and concerns about the future. Having a network of support during these times can be invaluable. It can be useful to think in advance about who can be relied on for support. It is important to consider those who can offer both practical help and emotional support.

Routines and social activities can also be disrupted by an illness or injury. There may be less time and fewer opportunities to engage in activities outside of the home. Attention to caregiving may result in an SSO taking time off work. Added responsibilities may also limit contact with friends and family. Altogether, access to much needed social support is lessened. Having realistic expectations about how care might be managed ahead of time can help prevent such outcomes.

When PSP have a brain injury or a posttraumatic stress injury (PTSI), they may experience behavioural changes. This can impact intimacy in couple relationships and shift additional responsibilities to SSOs. These types of injuries can also affect parent-child relationships. There may be heightened expectations for children to regulate their behaviours. It is important for families to support both the wellbeing of the PSP and individual family members.

Both short and long term injuries or illnesses can put financial strain on PSP couples or families. There may be temporary or permanent loss of income for the PSP. SSOs may cut back hours of paid work to provide care which further reduces household income. Reduced earning potential and expenses associated with care can cause financial strain. It is important for families to develop a financial plan to manage these risks.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

American Psychological Association. (2022). APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://dictionary.apa.org/

Bochantin, J. E. (2010). Sensemaking in a high-risk lifestyle: The relationship between work and family for public safety families. PhD Thesis. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Cox, M., Norris, D., Cramm, H., Richmond, R., & Anderson, G. S. (2022). Public safety personnel family resilience: a narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095224

Friese, K. M. (2020). Cuffed together: A study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 22(4), 407-418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355720962527

Helfers, R. C., Reynolds, P. D., & Scott, D. M. (2021). Being a blue blood: A phenomenological study on the lived experiences of police officers’ children. Police Quarterly, 24(2), 233-261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611120964954

Karaffa, K., Openshaw, L., Koch, J., Clark, H., Harr, C., & Stewart, C. (2015). Perceived impact of police work on marital relationships. The Family Journal (Alexandria, Va.), 23(2), 120-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480714564381

Landers, A. L., Dimitropoulos, G., Mendenhall, T. J., Kennedy, A., & Zemanek, L. (2020). Backing the blue: Trauma in law enforcement spouses and couples. Family Relations, 69(2), 308-319. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12393

Miller, L. (2007). Police Families: Stresses, Syndromes, and Solutions. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180600698541

Watkins, S. L., Shannon, M. A., Hurtado, D. A., Shea, S. A., & Bowles, N. P. (2021). Interactions between home, work, and sleep among firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 64(2), 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23194

An awareness of the ways that social media and news coverage might negatively affect your family is a great way to start the conversation. Talking about potential problems encourages families to work together to manage the risks. Certain sectors of PSP are criticized on social media in ways that are not easy to ignore, and this can have different effects on family members. Open communication allows family members to share their experiences and discuss ways to respond when issues arise (e.g., explaining the facts to trusted friends and encouraging children to report bullying to parents and school authorities).

Social media is how many people stay connected to friends and events happening around the world. It is a popular and useful mode of communication for all ages. No one wants to toss away their phone or shut down the internet but, like many things in life, moderation is key. There is some evidence that overuse of social media is linked to poorer mental health generally and PSP families have additional concerns. Misinformation about PSP can start a chain of negative social media posts that are disturbing. There is also a risk of seeing images of events that a PSP family member is responding to which heightens worry. It is unlikely that we are going to put a stop to misinformation and videos that go viral but changing social media habits can reduce your exposure.

The following checklist items are suggestions for anyone trying to limit online activity, but they may be of particular interest to PSP families who are targeted by or sensitive to certain social media content.

Begin by answering the following reflection questions in the space provided and then use the checklist to assess what you are currently doing to limit your exposure to social media and things you might want to try. You will have an opportunity to download and print your list to share with other family members.

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1088&context=dissertations

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.